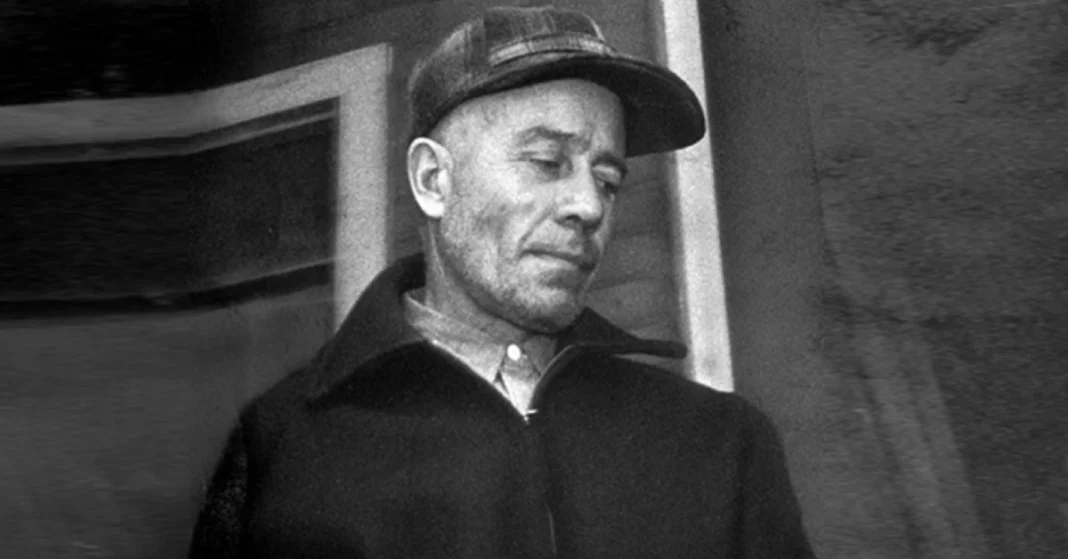

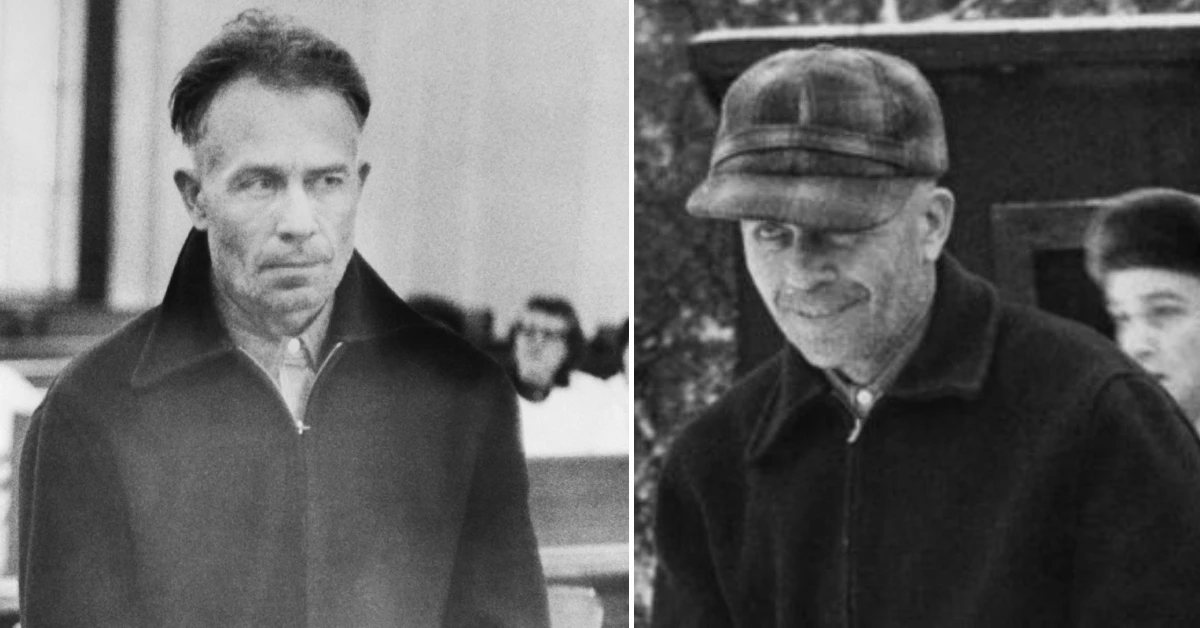

Henry George Gein lived forty-three years before dying under mysterious circumstances on May 16, 1944. His death certificate lists heart failure as the cause, but unexplained bruises on his head sparked rumors that persist eight decades later. While his younger brother Edward became one of America’s most notorious killers, Henry’s story remains buried beneath layers of crime documentaries and horror films.

Who Is Henry George Gein?

Born January 8, 1901, in La Crosse, Wisconsin, Henry George Gein entered a world vastly different from the one his brother would later terrorize. His parents, George Philip Gein and Augusta Wilhelmine Lehrke, had married just one year earlier. George worked as a carpenter and occasional tanner, while Augusta brought strong Lutheran beliefs and an iron will to their household.

Henry spent his early years watching his father struggle with alcoholism and unemployment. Augusta despised her husband’s weakness, often telling her sons that their father represented everything wrong with men. She ran a small grocery store to support the family, controlling every penny that came through their door.

Unlike his brother Edward, born five years later in 1906, Henry showed signs of independence from an early age. Neighbors remembered him as the more outgoing Gein boy, someone who could hold a conversation and look you in the eye. He inherited his father’s height and broad shoulders, standing nearly six feet tall by his teenage years.

Early Years in La Crosse, Wisconsin

La Crosse at the turn of the century bustled with lumber mills and river traffic. The Gein family lived in a modest frame house on the city’s north side, where German immigrants clustered in tight-knit communities. Henry attended the local Lutheran school, where teachers noted his average grades but excellent attendance.

The neighborhood children avoided the Gein house. Augusta discouraged friendships, believing other families would corrupt her sons with sinful ideas. She read Bible verses each evening, focusing on passages about damnation and the wickedness of women. Henry sat through these sessions, but neighbors later recalled seeing him slip out to play stickball when Augusta worked late at the store.

George Gein’s drinking worsened as his carpentry jobs disappeared. He’d stumble home from taverns, leading to screaming matches that echoed through thin walls. During one particularly violent argument in 1913, twelve-year-old Henry stepped between his parents. Augusta never forgot this betrayal, marking the beginning of a complicated relationship between mother and eldest son.

Life on the Plainfield Farm

The family abandoned La Crosse in 1915, purchasing a 195-acre farm outside Plainfield, Wisconsin. Augusta believed isolation would protect her boys from worldly temptations. The property sat six miles from town, accessed only by a winding dirt road that turned to mud each spring.

Henry adapted to farm life better than anyone expected. At fourteen, he could handle a plow and manage the dairy cows. He fixed broken equipment and built chicken coops without instruction. Local farmers hired him for harvest work, appreciating his steady hands and few words.

The Plainfield farm never prospered. Rocky soil and Augusta’s refusal to modernize equipment meant constant struggle. Henry worked dawn to dusk, trying to coax crops from stubborn fields. Edward helped when forced, but preferred staying inside with Augusta, who taught him to crochet and darn socks.

George Gein died in 1940, leaving his sons to manage the farm alone. Henry took charge of the outdoor work while Edward handled household chores. This arrangement suited Augusta, who grew increasingly dependent on her younger son’s devotion. Henry began taking more jobs in town, perhaps sensing the unhealthy dynamics developing at home.

Brotherly Bonds: Henry and Edward

The Gein brothers shared a bedroom for over thirty years, yet remained strangers in many ways. Henry enjoyed physical work and simple pleasures like fishing. Edward lived in his imagination, reading pulp magazines and anatomy books by candlelight. Despite their differences, they rarely fought, bound together by their mother’s domineering presence.

Childhood Fire Incident

In 1917, a fire nearly destroyed the Gein farmhouse. Six-year-old Henry pulled his younger brother from their smoke-filled bedroom, suffering burns on his arms. Augusta praised God for saving her boys but never thanked Henry directly. This pattern continued throughout their lives—Henry protecting Edward while Augusta lavished affection on her younger son.

Family Dynamics Under August Gein

Augusta ruled through fear and manipulation. She assigned Henry the hardest farm tasks, claiming physical labor built character. Edward received gentler treatment, helping with cooking and cleaning. She told neighbors that Henry resembled his worthless father, while Edward had inherited her superior qualities.

Henry began questioning Augusta’s teachings in his thirties. He mentioned finding a girlfriend to fellow farmhands, speaking of someday having his own family. Word reached Augusta, who launched into sermons about lustful women destroying decent men. Edward always took their mother’s side during these arguments, leaving Henry increasingly isolated.

By 1944, tensions peaked. Henry talked openly about leaving Plainfield, maybe heading west, where nobody knew the Gein name. He’d saved money from his town jobs, keeping it hidden from Augusta’s prying eyes. Some historians believe this growing independence triggered the events leading to his death.

Tragic Death: Circumstances & Aftermath

On May 16, 1944, Henry and Edward fought a marsh fire threatening their property. Such fires commonly plagued Wisconsin farms during dry springs. The brothers separated to battle different sections, a decision that proved fatal.

Edward reported his brother missing as darkness fell. He led search parties directly to Henry’s body, despite claiming they’d lost contact hours earlier. Henry lay face down in an area already burned over, with no evidence of smoke in his lungs. Most disturbing were the unexplained bruises on his head, inconsistent with fire-related injuries.

The coroner ruled it an accidental death by asphyxiation. No autopsy was performed. Edward appeared distraught at the funeral, while Augusta maintained her typical stone-faced composure. She told mourners that God had called Henry home, perhaps saving him from a sinful life in town.

Police accepted the official explanation without investigation. Small-town authorities knew the Geins as odd but harmless. Nobody imagined quiet Edward capable of violence. This assumption would prove tragically wrong thirteen years later when police discovered the horrors inside the Gein farmhouse.

Legacy Overshadowed: Why Henry’s Story Faded

Henry George Gein vanished from public memory the moment his brother’s crimes surfaced in 1957. Newspapers focused on Edward’s grave robbing and murder, turning Plainfield into synonymous with horror. Henry became a footnote, mentioned only to establish Edward’s troubled family background.

True crime writers speculated about Henry’s death after Edward’s arrest. Some theorized that Edward killed his brother to eliminate competition for Augusta’s affection. Others suggested Henry discovered disturbing behavior and threatened exposure. Without evidence, these remain theories, though the suspicious circumstances fuel ongoing debate.

Hollywood adapted Edward’s story countless times, inspiring characters from Norman Bates to Buffalo Bill. Henry never appears in these narratives beyond brief mentions. His ordinary life and mysterious death can’t compete with his brother’s sensational crimes for audience attention.

Recent genealogy websites have revived interest in Henry’s story. Amateur researchers dig through census records and newspaper archives, seeking facts about the forgotten Gein. They’ve uncovered employment records showing Henry worked for respected Plainfield families who remembered him as reliable and polite.

Remembering Henry: Grave, Records & Remembrances

Henry lies in Plainfield Cemetery, his grave marked by a simple stone reading “Henry G. Gein 1901-1944.” Visitors leave flowers, drawn by curiosity about the Gein family tragedy. His plot sits several rows from where Augusta was buried in 1945, and far from Edward’s unmarked grave in the same cemetery.

Official records paint a sparse picture. His birth certificate from La Crosse County shows a normal delivery at home. School records indicate average performance through eighth grade. The 1920 and 1930 censuses list him as a farm laborer, living with his parents. No marriage license or military service records exist.

Local historians preserve scattered memories. Marie Hoeft, who hired Henry for farm work, told researchers in the 1980s that he seemed “lonely but decent.” Store owner Frank Worden recalled Henry buying supplies, always paying cash and avoiding small talk. These fragments suggest a man trapped by circumstances, yearning for a life beyond his mother’s reach.

Modern Plainfield acknowledges its dark history through careful tourism. The Gein farm burned in 1958, leaving only the foundation. Visitors sometimes leave items at Henry’s grave—coins, wildflowers, notes asking why he stayed so long. Perhaps they recognize a universal story in Henry George Gein: the eldest child sacrificing dreams for family duty, paying the ultimate price for loyalty to those who couldn’t love him back.

His death at forty-three ended any chance for escape or redemption. Whether murdered by his brother or killed by random misfortune, Henry died as he lived—overshadowed and alone. Yet his story resonates precisely because of its ordinariness. Unlike his infamous brother, Henry represents countless forgotten souls who work hard, follow rules, and disappear without notice from history’s pages.